“Right from the beginning you knew this was different”

‘28 Days Later‘ is often attributed for reinvigorating the zombie movie genre through the introduction of the running zombie, which has become a staple in pretty much every zombie film since, including ‘Dawn of the Dead’ (2004), ‘REC•‘ (2007), ‘World War Z’ (2013), ‘Train to Busan’ (2016) and many more. However, whilst the film did indeed popularise the running zombie, it had in fact already been done as far back as Umberto Lenzi’s “Nightmare City” (1980).

When 28 Days Later was originally released in 2002 I was working around Wembley and remember seeing the billboards up with their bold, graphic, red and black biohazard stencil look. I first saw the film fresh, having seen not a single preview or trailer, so went in with no expectations whatsoever. What struck me most from the outset was how much closer the film felt than anything like it before. It was set on the very streets where we’d go to clubs like The End just off Tottenham Court Road, where Jim would set off the alarm of an abandoned car (pictured above). The film also had a very authentic British feel to it. Unlike the wooden, middle-class, rom-com guff of Richard Curtis, 28 Days Later was raw and aggressive and something I could truly envision on the streets of London. In fact, it is one of very few films that actually depicts London authentically. The only others I can think of are ‘The Day the Earth Caught Fire‘ (1961), ‘Withnail and I‘ (1987), ‘Tony London Serial Killer‘ (2009) and ‘Skyfall‘ (2012).

Parallels can be drawn with movies such as ‘The Omega Man’ (1971) which preceded it, but the film felt much removed from the high-budget Hollywood gloss of predictable characters, generic casting and over-dependence upon VFX. Boyle also dispensed with some real-world logic in favour of more striking and charged visuals. For example, there is no logical explanation as to why no bodies are present during the film’s opening. This was a conscious decision in favour of achieving something more abstract and stirring. Some of its visuals would also echo scenes of 9/11 which had occurred during its production though not a direct point of reference.

“It was coming in through your windows”

Danny Boyle is a national treasure who has consistently pushed the envelope and developed his own wall-breaking style where reality can be subverted yet simultaneously contained within the rules of the respective filmic world. Through this style Boyle enables the subjects of his films to momentarily escape the normal bounds of reality and delve into an entirely different space regardless of whether they’re confined on a spaceship, trapped under a boulder or down Scotland’s worst toilet. I’ll never forget when our school screened the overdose scene from “Trainspotting” in an assembly on drugs and how none of the other kids understood how the character of Renton sinking into the carpet was a visual representation of him sinking into his intoxicated state. Yeah, I didn’t fit in with Watford kids. They were all idiots.

28 Days Later is undoubtedly a Boyle/DNA film that enlists many of his dream team including writer Alex Garland, actor Cillian Murphy whose career this film launched, composer John Murphy and sound designer Glenn Freemantle. One member of the team who was absolutely pivotal in this production however was cinematographer, Anthony Dod Mantle. A dogma 95 guy and a pioneer in the use of digital cameras over conventional 35mm rigs, Dod Mantle would film some scenes from 28 Days Later using a Cannon XL1, a handheld DV camera which can be picked up today for as little as £270.

The inclusion of a handheld DV camera gives the production as a whole a hit of The Blair Witch Project (1999) effect, where camera shake can be used to energise a scene and the lo-fi quality provides a more real-world visual experience. The JJ Abrams-produced monster movie “Cloverfield” (2008) owes a debut to Dod Mantle’s work in this respect. Digital cameras produce more jagged visual artefacts compared to softer 35mm film and this is used to incredible effect in the scene where the infected attack Jim’s house, with the fragments of a smashing window seeming razor sharp and every splatter of blood feels all the more visceral. The final element that perfects the violence of the imagery is the shutter speed. By shooting at high shutter speed the image loses the smooth blur we normally associate with movies and it achieves an even more sharp and subtle stroboscopic look. The culmination of this technical approach has an outstanding effect with Private Mailer’s brutal rampage in the final act.

“You’ll never hear another piece of original music”

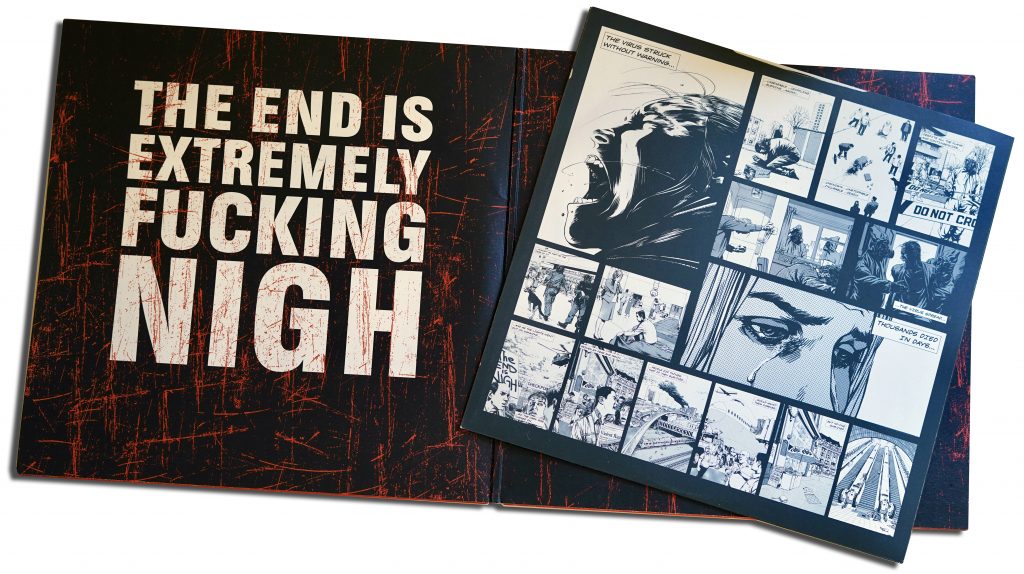

With virtually every modern British horror movie there is always some area of compromise. Amateur acting, over-ambitious use of effects or crappy music – there is always somewhere they drop the ball. However, 28 Days Later delivers spectacularly in the sound department. I was working as a music distributor when the film came out and nabbed myself a copy of the soundtrack on vinyl and it may well have the coolest artwork of any record I own (pictured above). John Murphy has worked with Danny Boyle on a number of films and every time his work perfectly hits the mark. For the most part, it is comprised of very raw, pounding indie rock tracks that provide heart-thumping tension to the visuals and extenuate the grimy, rubbish-strewn, British feel of the movie. In counterpoint are more melancholic pieces that emphasise a sense of sad loss and solitude. When producing the original music for “Crobar: Music When the Lights Go Out” (2020) we presented composer Hiraeth with this soundtrack as a reference to the feeling we wanted for the desolation of London due to Covid-19. As well as the original music are licensed tracks “AM 180” by Grandaddy which provides an upbeat lift midway into the movie, Brian Eno’s “An Ending (Ascent)” and “Season Song” by Blue States that rolls with the credits – a really nice track with the rich instrumentation that became their trademark sound featuring vocals from the St Winifreds Choir. As a record the soundtrack not only comes across as British (with the exception of Grandaddy), in keeping with the rest of the film, but also very complete and accomplished in its own right.

“It’s in the blood”

28 Days Later shows the important role that motion and its speed play in the language of cinematography and demonstrates that camera choice can be as much a matter of aesthetics as of economics. Sometimes the lesser expensive camera could be the better creative choice. There are those who attempt to take on the blockbusters without the means to do so only to come off hackey but when you embrace the inherent creative possibilities of even the most rudimentary equipment or unorthodox techniques, that is when you can truly start to innovate.