Christmas morning 1989. It was so early it was still as dark. I clamber out of my bunk bed with the room illuminated by the glow of a small portable television where my brother squeaked a stiff black joystick and clicked its red plastic buttons. ‘Ghouls’n’Ghosts’ on a second-hand 48K ZX Spectrum. I stood in my pyjamas, captivated by the yellow and black image of a knight fighting his way through the darkness of a rainy, nighttime graveyard with just the occasional sound effect to break the imposing silence of the game world. This was so much more than “just a game” to me. This was an experience as significant as any film or song, but one with its own unique feel. Just as we had the wonky video tracking of VHS, or the crackle of vinyl, with games you had the mad screech of a tape loading or the blow on the cartridge that wouldn’t load. Games as an artistic medium continue to influence my cinematography. When using a slider or any horizontal motion, it’s impossible not to recall the depth of the multi-layer parallax scrolling that gave life to the opening Green Hill Zone of ‘Sonic the Hedgehog’, or ‘Streets of Rage’. More recently the Chinese’s Room’s ‘Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture’ served as a blueprint both for the use of light in Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Leavesden Asylum Story, but also Jessica Curry’s incredible operatic score, which I insisted my composer and singer study in great detail, with an early concept trailer borrowing the track ‘All of my Birds‘.

Who’s who of horror

I could talk all day about games just as I like to talk about any art form, so what better place to start than one of my all-time favourite and most influential series, Silent Hill. I am an unashamed Silent Hill fanboy. I own all eight games of the main series, the first three soundtracks, a Toluca Lake t-shirt and a copy of the movie on DVD with my cinema ticket stub from the first showing on release day tucked in the cover. Silent Hill was Konami’s response to Capcom’s Resident Evil, which had taken the survival horror niche to the mainstream. But where Resident Evil had the classic zombie tropes and jump scares from the movies of George A Romero’s ‘Night of the Living Dead’, Silent Hill would take an alternative direction of surreal psychological horror that would affect the player on a subconscious level.

The opening cinematic of Silent Hill blew our minds when it first did the rounds on Playstation demo discs back in 1999. These graphics were incredible by the standards of the time. Never before had we seen something that cinematic come from a game. The visual direction of a scene where the protagonist Harry Mason and his daughter Cheryl crash their car when swerving to avoid a child on the nighttime road into town takes its cues straight from David Lynch’s Lost Highway. The game’s quirky characters and surreal elements come directly from Twin Peaks, his cult TV drama series that followed an investigation into the murder of a teenager in a small mountain town that starts to reveal layers of the strange and otherworldly.

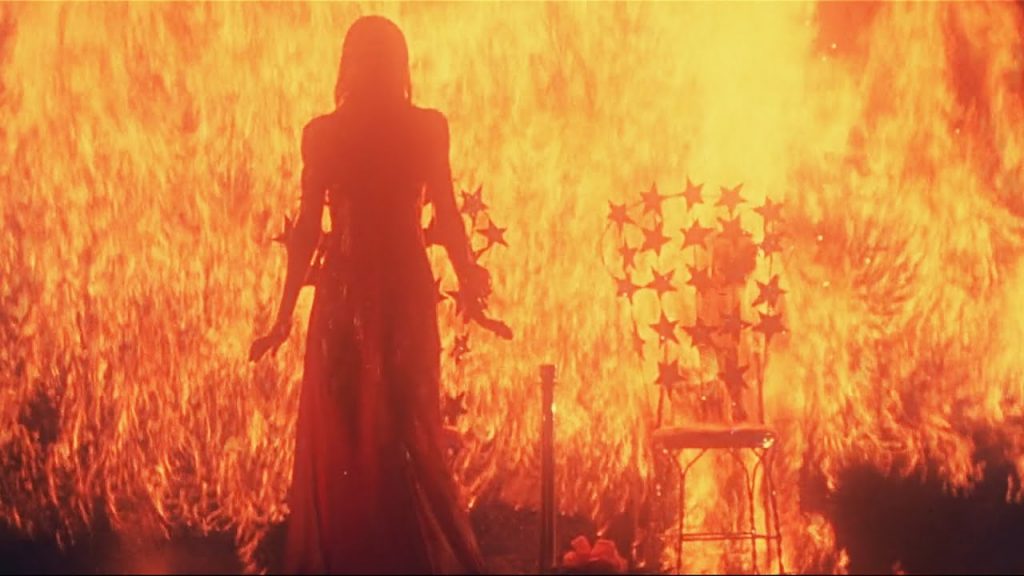

Silent Hill is very much a ‘who’s who’ of horror references with the streets of the town even named after the writers whose work influenced its creators including Robert Bloch, Ira Levin, Richard Materson, Lewis Carroll and Dean Koontz. But the most notable influences are films like Carrie, which studies a psychic coming to power, Stephen King’s The Mist, about a town that becomes shrouded in a dense fog concealing otherworldly creatures, and of course the aforementioned work of David Lynch.

A story of an enchanted town

For those that don’t know, Silent Hill is the story of a remote, mountain resort town, which is bestowed with an ancient supernatural power. Within the town a religious cult known as ‘The Order’ perform a sacrificial ritual on a child, Alessa Gillespie, who is a powerful psychic, in an attempt to impregnate her and birth their god. However, in the extreme trauma of the ritual, Alessa’s psychic energy starts a fire and she splits herself between her real, burned body, trapped in a nightmare, and her pure soul which is reborn in the real world and adopted by a man named Harry Mason. In doing so she corrupts the town, enabling Silent Hill with the ability to summon tormented people and confront them with twisted projections of their own nightmares and trauma. The game then follows Harry’s quest to try to find his daughter and uncover the secrets of the enchanted town. It is worth mentioning that the occult symbolism in Silent Hill is second to none with extensive time and research invested into studying a whole host of exoteric religions throughout time and from across the globe.

What set’s Silent Hill even further apart from Resident Evil is how the town feels legitimately like it had been lived in. Where Resident Evil has bizarre puzzles and doors requiring strange combinations of keys to open, Silent Hill has houses with food rotting in fridges, piles of trash, and some very dark subplots about drug addiction and exploitation.

Team Silent

Silent Hill was created by Konami Entertainment’s Team Silent of which key members included director Keiichiro Toyama, musician and sound designer Akira Yamaoka and art designer Masahiro Ito. These three guys were nothing short of god-level.

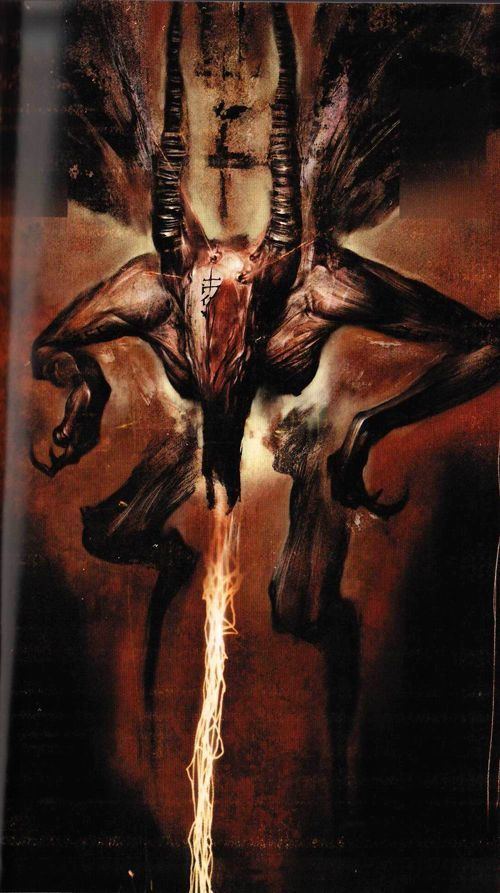

Masahiro Ito is my favourite artist of all time. His surreal work could be compared to HR Giger or Francis Bacon in how it melds the mechanical with fleshy, sexualised imagery. Ito physicalises the collapse of the modern world and the fear that surrounds it including war, disease and sexual violence. It is very much Ito’s vision that makes Silent Hill so uniquely scary for modern audiences. Whilst past eras of horror spoke of wolves, witches, ghosts and vampires in an attempt to tap into the zeitgeist of the time, the fears of modern audiences are things like cancer, birth deformity, rape, nuclear and chemical warfare. Ito’s most iconic work would appear later in the series, but his visceral design in the first game places you in a dark, fleshy, metallic pit that you instinctively want to escape from.

Akira Yamaoka, one of, if not the most highly revered game music composers of all time, gave a one-two punch which has never been matched. His musical score, which would draw upon Angelo Badalamenti score for Twin Peaks, gives you the warm acoustic guitars that ground you in this tranquil mountain town, then crosses into a strange and unearthly place with janky atonal church organs and dreamy symphonies as well as the creepy spaghetti guitar of the main theme. The counterpoint to this is the sound design, which is amongst some of the finest industrial sound art ever made. So good was his score that it was lifted in its entirety for use in the 2006 film adaptation.

What Keiichiro Toyama did was truly alchemy. He took the art of Masahiro Ito and the sound of Akira Yamaoka plus all the other influences and melded it into something the world had never seen before. What really stands out to this day is the ingenious way in which Toyama applied this material to the technology of the PlayStation 1. For example, in Silent Hill you explore a large, open-world town, however, the PS1 had a limited draw distance, only able to render objects that were a short distance from the player. So to get around this Toyama shrouded the town in the mist from Stephen King thereby concealing this technical limitation whilst embedding the world deeper into the source material. Another design choice was, rather than copy Resident Evil’s static pre-rendered backgrounds, Silent Hill would be rendered in fully 3D models with both dynamic and fixed cameras as well as dynamic lighting. The combined effect of Yamaoka’s industrial score and Ito’s art design rendered in rough, flickery, 32bit, texture-mapped polygons is something to behold to this day. I will never forget the first time I saw a clip on TV of Harry Mason running around the halls of Midwich Elementary. It is what I describe as “beautifully ugly”. There’s just something so nightmarishly visceral and gritty about the effect. And that moment where you venture beneath the clock tower and remerge to the sound of the air raid sirens to find everything has changed just gives you chills.

The Silent Hill Movie

Christophe Gans 2006 movie adaptation is the best video game movie yet. Some of the first scenes of otherside Silent Hill were copied directly from the game with a Playstation on set for reference. However, it is a film that I would love to edit to take out the unnecessary prologue and to also remove all the scenes with Sean Bean which were added later after the studio decided the cast comprised of all female leads needed a male. This was a mistake. But I’ll never forget rushing down to the cinema on launch day for the first screen and sitting there in awe at the scenes of the demon grey children horde, the armless men shambling down the foggy hillside, the pyramid head skin rip and otherside Alyessa dancing in a rain of blood. Very decent, although the less said about the two bit sequel the better.

I could talk about Silent Hill all day. In fact, I might have to write a follow-up talking about the various sequels. The aesthetic of decaying buildings enveloped in fog or twisted, sexualised monsters in a world of cages and flesh is ultimately compelling. There is just so much to say as it is many layers of art intersecting to deliver a masterpiece, one that continues to inspire across the creative world today. In fact, my first ever attempt at filmmaking whilst studying a degree in creative music technology back in 2007 was a deeply Silent Hill-inspired short.

As we see more of those who grew up with it taking the director’s chair in films, games and the arts, I am certain that we will see Silent Hill’s influence felt for decades to come.